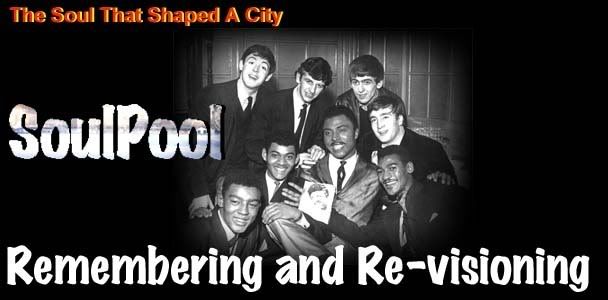

This article is based upon the remarkable research of the Soulpool website, conducted by Steve Higginson , David Pendleton and others. Basically, Soulpool is creating a detailed social and cultural history of the musical roots of Liverpool, and using oral history they have been able to present a very different version of the origins of the Mersey Sound. I don't think there is any similar project of such depth online concerning this aspect of British social history. So, once you have finished reading my short(er) post to wet your appetite, follow the links over to Soulpool to read the rest of the story that forms one of the most important chapters in the history of Soul Britannia...

This article is based upon the remarkable research of the Soulpool website, conducted by Steve Higginson , David Pendleton and others. Basically, Soulpool is creating a detailed social and cultural history of the musical roots of Liverpool, and using oral history they have been able to present a very different version of the origins of the Mersey Sound. I don't think there is any similar project of such depth online concerning this aspect of British social history. So, once you have finished reading my short(er) post to wet your appetite, follow the links over to Soulpool to read the rest of the story that forms one of the most important chapters in the history of Soul Britannia...Trying to track down the origin point for a social phenomenon is intrinsically difficult, and there will always be the isolated example that acts as an exception to the rule. However, the history of Merseyside offers evidence that it is amongst the earliest British communities to have ready access to and develop an appetite for American r&b music. From this appetite, a new musical movement was formed, which then went on to transform music in Britain and then impact across the world...

We will all think we know this story of course. Yet while four loveable moptops were indeed responsible for the final breakthrough of Merseybeat into popular success in 1962, their careers alone do not explain the origins of this new sound.

Liverpool's black history, of course, is a long one. Both free and unfree, black people have been living in Liverpool for 400 years. As Britain's principal slave-trading port for over a century, it surpassed Bristol and London. Even after abolition of slavery in the British Empire, Liverpool's dock workers were among the most vociferous in their support for the Confederacy during the American Civil War, being at that time dependent on the southern cotton trade. Throughout all this time and beyond to living memory, Liverpool was the principal port of access to the commerce of the Caribbean.

Poverty and casual racism often colluded to ghettoise these communities geographically, for example in Toxteth, Liverpool 8, despite the lack of racial codes. As in other areas of Britain, the sign in the window of rooms to let would frequently read, "No Irish, No Gypsies, No Blacks." However, in a busy port like Liverpool, there was work to be had in boom times, and throughout the C19th, racial solidarity could be found in workers' movements such as the Chartists (William Coffey being one of the prime leaders in London), and later in the trade union movement. Of course, in times of slump, more selfish motives could rise to the surface. Such a time occured in 1948, after a wartime rise in the black population, due to the call for qualified nurses and doctors to aid the mother nation during its time of crisis. In the post-war austerity era, it became easy for people to accuse black Liverpudlians of taking jobs that belonged to white people. White rioting occured through Toxteth in that year.

So, in Liverpool by the late 1940s, before even the Windrush generation, the black community was larger and more established than in other cities outside of the major seaports. It stands to reason that there was already a growing number of musicians with both Caribbean and African influences through the 1940s and 50s. It was however, according to oral histories, quite difficult to find venues to play in, in large part due to the long-running Musicians' Union ban on any American bands playing in unionised venues. This ban was in large part a reaction to 'negro bands', as the union put it, and affected local musicians as much when combined with the casual segregation of most Liverpool venues in the 40s and 50s. Right up until the late 1950s, most licenced clubs were folk orientated in central Liverpool. Local halls such as the Nigerian, the Sierra Leone, and the All Nations, built by the Toxteth community, or the White House pub, were some of the few opportunities to perform and to go in relative peace to hear what was still unfamiliar music to the majority of Britons.

Liverpool's position as a major seaport made it open to other influences, from the late 30s onwards. Merchant seamen who found themselves travelling to the Caribbean and to the United States had the opportunity to take shore leave and wind down in the local nightlife. They began to get a taste for the very different kinds of music they encountered there. Soon they were seeking out record stores in those places, and bringing their finds in country, jazz and later r&b home with them. To the Liverpudlians back home, these 'Cunard Yanks', as they were known, often appeared outlandish, somewhat strange, when they began to congregate and play this discover'd music at their hangouts. Their clothing would seem outlandish also, described by Cunard employee Tony Dwyer as being manily African-American fashions, such as zoot suits, full drape jackets, and very tight bottoms to the trouser leg, and which Steve Higginson describes from a slightly later era as being the smart, sharp suits and button-down shirts being worn by the American r&b artist Billy Eckstine, and uncannily similar to the 'mod' fashion that would emerge in Europe and Britain nearly six or seven years later. Some, like sailor Ian Gilmour, came home in the late 50s and established clubs in Liverpool, at least tapping into the rock and roll boom and providing a atmosphere tolerant to r&b and jazz as well as the usual rock and roll. However, some other historians strongly dispute the influence of merchant seamen on Merseybeat bands themselves, stating that it was a world in which those bands rarely interacted. As this is a big debate, I will come back to it in another post.

Record stores in Liverpool began to stock this new music in the 1950s. When the rock and roll boom hit Britain in the late 50s, there was already this established influence. Teenage skiffle enthusiasts and banjo players in Merseyside were able to satisfy their curiosity when they encountered names such as Elmore James, Sleepy John Estes, Larry Williams or Arthur Alexander alongside Elvis or Buddy Holly, in a way that other British rock and rollers would not so easily. However, there was something else that allowed the growing army of scouse rock'n roll bands to deepen their understanding and experiences of r&b.

Up with rockers like Rory Storm or the Hurricanes, the Merseybeat scene was dominated by

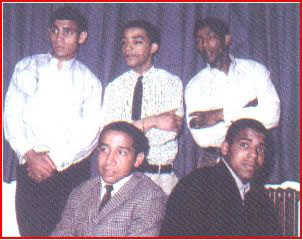

homegrown artists playing their own authentic r&b. Derry Wilkie, Sugar Dean and Colin Areety jumped onstage when Little Richard played Liverpool, and were accepted for their talents and the enthusiasm of the local crowd. A number of big American r&b artists made it their business to tour to Liverpool, where they were assured of a good audience - one recent commentator on this blog, Bill Mitchell, remembers with fondness the time Joe Turner performed and came down into the audience during the interval to chat and have a drink with the people. The Valentinos, named for their American namesakes, and other local groups were digesting and recreating the American vocal harmony group sounds of the late 50s and early 60s. The Chants were also writing and performing in this vein. When four befringed lads came by to hear them play, they went back to their manager Brian Epstein to beg to play behind The Chants as their backing band. When The Chants came to The Cavern, this is exactly what the Beatles did, despite Epstein's obvious displeasure that his band were being upstaged.

homegrown artists playing their own authentic r&b. Derry Wilkie, Sugar Dean and Colin Areety jumped onstage when Little Richard played Liverpool, and were accepted for their talents and the enthusiasm of the local crowd. A number of big American r&b artists made it their business to tour to Liverpool, where they were assured of a good audience - one recent commentator on this blog, Bill Mitchell, remembers with fondness the time Joe Turner performed and came down into the audience during the interval to chat and have a drink with the people. The Valentinos, named for their American namesakes, and other local groups were digesting and recreating the American vocal harmony group sounds of the late 50s and early 60s. The Chants were also writing and performing in this vein. When four befringed lads came by to hear them play, they went back to their manager Brian Epstein to beg to play behind The Chants as their backing band. When The Chants came to The Cavern, this is exactly what the Beatles did, despite Epstein's obvious displeasure that his band were being upstaged.This is how bands like The Beatles, who were also the songwriters behind hits for many other Merseybeat bands, were able to listen to complex vocal harmonies in r&b firsthand, and learn how to incorporate them into their guitar-based rock and roll.

They encouraged Brian Epstein to sign up The Chants along with many other Merseybeat bands in 1964. However, you get the impression that he had little enthusiasm for promoting them. Ironically, Epstein got them a record deal with ... Pye Records, the well-meaning but slightly out-of-their-milieu label of Jimmy James and The Vagabonds and later Geno Washington & The Ram Jam Band also. The sound of the black r&b groups of Liverpool had some similarities with the Merseybeat sound, but it is clearly pure r&b, and different enough that the record-buying public, obsessed with Beatlemania, passed it by for the next long-haired Mersey group single. Meanwhile, other enthusiasts of American r&b, in other parts of Britain, were unaware of what was on offer to them in Toxteth, in those dark days before the internet. Micks and Keiths and Erics (both Bs and Cs) continued to think they had to go to Detroit and Chicago to find the gritty r&b they had encountered.

Here is a little taste of the early Chants, written by Eddie Amoo, as would have influenced Liverpool beat groups. Later, I will be sharing some of the transformations that The Chants and other black British groups went through to try to gain commercial success to match their talents.

The Chants - I Don't Care (1963)

Information for this post came from the Soulpool website - who go into much greater detail than I have here on all these phenomena. It is a must-read if you are interested in the story of Soul Britannia! Much information about the Chants comes from articles and photos collected by Bill Harry, journalist and author of the site Mersey Beat. I have also learnt some interesting things from the websites of Colin Dilnot, who has been kind enough to mention this site several times in recent months. In Dangerous Rhythm should be part of everyone's weekly blog trail. Recently, on his Soul of Liverpool blog, Colin announced the sad passing of Vincent Ismael, a member of Liverpool soul group The Harlems.

No comments:

Post a Comment