1956. Back to Soho. Home of the jazz clubs and the skiffle clubs. Above The Roadhouse pub on Wardour Street, tired of skiffle and trad jazz, Cyril Davies and Alex Korner are setting up a club night, playing the blues. The night is called the Blues & Barrel House Club. The band is called Blues Incorporated. Who knows if anyone will come?

1956. Back to Soho. Home of the jazz clubs and the skiffle clubs. Above The Roadhouse pub on Wardour Street, tired of skiffle and trad jazz, Cyril Davies and Alex Korner are setting up a club night, playing the blues. The night is called the Blues & Barrel House Club. The band is called Blues Incorporated. Who knows if anyone will come?They come. Big Bill Broonzy and Otis Spann even come down to hear and play, and stay at their houses while they are in town.

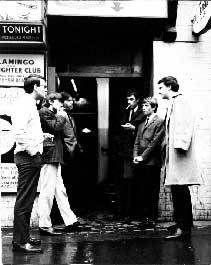

They've come down from the Cold War US airforce bases around London, where they've been playing for the servicemen - the only place up to then you could hear the blues in Britain. Like many GIs, they come into Soho, looking for entertainment. First to clubs like the Americana for jazz; then on to Wardour Street to the Barrel House and finally down to the basement club The Flamingo for modern jazz and latest r&b singles from Ray Charles and Lee Dorsey. Mixing with student trad jazz fans, being beatnik in old jumpers and scruffy trousers, the GIs cut a style in suits and ties. Some of the skifflers and jazz musicians are interested: Zoot Money, Georgie Fame And The Blue Flames, Chris Farlowe and the Thunderbirds, are listening and learning.

They interest the younger kids too. From all over London they come to hang out in Soho, young mostly working-class boys who are fascinated by everything American, but can't find it in austerity Britain, can't dress like that, but they try and put on an attitude. They are not going into National Service like their older brothers, the Teds, and coming out aged and conformist. Thanks to the self-same GIs and thanks to mutually assured destruction, the country doesn't need their services. These boys are able to go to work, earn their money, buy clothes, go out, and spend it how they want. They aren't as rich as they make out - you can do a lot on the HP. They want a new kind of life all the same.

At the Flamingo, they can meet real Americans. The GIs can sell you buttoned Levi's for a fiver.

Where do you get those suits, those shirts? They just don't exist in the high street. So you need to find a way to alter things yourself. First, find something you like at Marks & Sparks, or C&A. Round the corner from The Roaring Twenties Club, where blue beat mixes with r&b from 1961, the tailor at Newmans on North End Road will make you a suit with the 'Billy Eckstine collar', or help you get the perfect 'Italian' drop to your trouser. Go to the cinema, and there are new ideas every week. La Dolce Vita with Marcello Mastroianni, Shoot The Pianist with Charles Aznavour, Rocco And his Brothers with Alain Delon, the New Wave. Always new, different, modern, changing. Think of a style, and take it to John Stevens in Fulham, Bilgorri in Bishopsgate. Now show it off at the clubs...

It's not just about the clothes anymore. It's about the music. The GIs have records to sell as well. Better than trad jazz, or skiffle, or Cliff Richard's tame rock and roll. Its a handy extra income, and a way to offload belongings before returning to the States.

March 17th 1962.

The Barasque Club, opposite Ealing Tube Station. Art Wood, singer with Blues Incorporated, asks if the owner wants a new resident band, a blues band. He agrees. Davies and Corner open a new club night, and the faces start to appear from other pockets of London, young, fashion-conscious, a little arrogant, interested in the new sounds. Soon, another club offers them a residency - The Marquee Club, at that time on Oxford Street.

Clubs in 1962 mean live music, and there are a small but growing coterie of young people who have absorbed the r&b records they have bought, and are starting to play. You'd find Brian Jones in the audience at the Marquee, Mick Jagger taking a turn as a singer with Blues Incorporated, Eric Clapton and other Yardbirds not far behind, Chris Farlowe and especially Georgie Fame and his Blue Flames turning from jazz and skiffle towards r&b at The Flamingo.

Clubs in 1962 mean live music, and there are a small but growing coterie of young people who have absorbed the r&b records they have bought, and are starting to play. You'd find Brian Jones in the audience at the Marquee, Mick Jagger taking a turn as a singer with Blues Incorporated, Eric Clapton and other Yardbirds not far behind, Chris Farlowe and especially Georgie Fame and his Blue Flames turning from jazz and skiffle towards r&b at The Flamingo.A local phenomenon amongst young men and women in London, looking for whatever the latest styles and trends are, trying to make their own identity, has encountered a club life suited to the tastes of GIs and Caribbean-Britons, and heard a music that intrigues them. Something similar is happening in some other places, in Liverpool, and in East Anglia, in smaller towns near other airforce bases. People visiting the London nightlife are bringing back the news and the new sounds to towns across the south. The rest of the country hardly know anything about it, but soon it will become a national youth culture...

Here are some tunes from Blues Incorporated in the early years. The first is taken from an LP recorded live at The Marquee Club in its first few months back in 1962, and released on Ace Of Clubs. The second is the b-side of Blues Incorporated's first single, released in 1963, many years after the formation of the group. I think this reflects the assumptions in Britain at the time that the priority for a band was playing live, and perhaps also that for many British blues musicians, they did not fully consider the idea that they could make records like their own idols. This was about to change dramatically as the recording industry, soon to be bowled over by the public fervour for The Beatles, awoke to the potential of British beat.

Alexis Korner & His Blues Incorporated - Rain Is Such A Lonesome Sound (LP 'R&B From The Marquee Club' ACL1130) 1962

Alexis Korner's & His Blues Incorporated - Please, Please, Please (B-side of Parlophone R 5206) 1963

Information gathered from The Georgie Fame site, The Marquee Club website, The British Beat Boom website (very good index of many bands), and from Mod: A Very British Phenomenon by Terry Rawlings.