Time for some more Soul Britannia, and we are returning to Toxteth, Liverpool, to continue the story of The Chants...

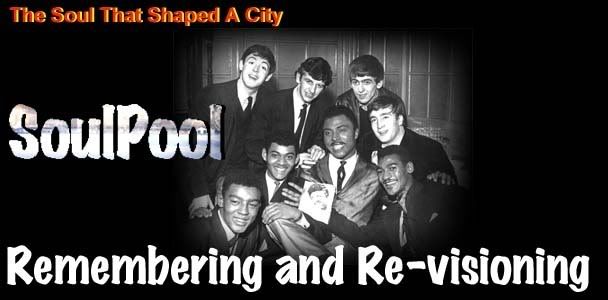

Time for some more Soul Britannia, and we are returning to Toxteth, Liverpool, to continue the story of The Chants...As the excellent Soulpool website explains, and as discussed in a previous post, the musical heritage of Liverpool and the origins of the Merseybeat explosion have deep roots. Some of those roots were drawing nutrients from the singing groups and bands of Toxteth, Liverpool 8, an area of Liverpool with a large Caribbean population long pre-dating the Windrush generation. Local halls such as the Nigerian, the Sierra Leone, Stanley House, the Rialto Ballroom, and the All Nations, built by the Toxteth community, or the White House pub, were popular venues for local people to hear r&b, and a big draw to black GIs from RAF Burtonwood. Some of the key r&b acts of the late 50s and early 60s - Derry Wilkie, Sugar Dean and Colin Areety, The Sobells, The Conquests, The Poppies and The Chants - all came from Toxteth.

It was in this environment that The Shades - Joe and Edmund Ankrah, Nat Smeda, Alan Harding and Eddie Amoo - honed their craft, enough to be noticed by the young and eager Paul McCartney, who met Joe Ankrah in a New Brighton ballroom, and invited them to come along to The Cavern. The other Beatles were equally enthusiastic, and they decided to play behind as the backing band. The response from the audience was enough to convince Epstein to sign the renamed Chants, but it would not be the magical mystery tour of fame that they had expected. Rather, they would take the long and winding road to the real thing...

Despite Epstein's management, nothing seemed to happen for The Chants through early 1963, and as they continued to miss the wave of the Mersey Sound, they managed to convince a clearly-disinterested Epstein to release them from their contract. They had to go to Manchester to find Ted Ross, who arranged a record deal with Pye Records in London in April 1963. Such a journey to find musical success was not at all unusual in the British music industry, which was overwhelmingly centred on the capital for many decades. It would, however, leave The Chants particularly isolated from the musical influences and musicians that underpinned their vision for themselves.

The Chants - I Could Write A Book

The Chants - I Don't Care

Pye Records, a big industry hitter which was trying to embrace this new youth fashion for 'beat' music, were not an r&b label. 'They had no idea what to do with a black doo-wop group, they just had no idea.' recalled Eddie Amoo in an interview. While other r&b groups, for example The Kinks, could turn up at Pye and just start playing the way they wanted to sound, The Chants, as a harmony singing group, suffered from the need to rely upon the hired musicians and arrangements designed by people unfamiliar with all of the nuances of doo-wop and r&b. Eddie in another interview explained the impact this had upon them:

"But in that era - late 60s, the very early 70s - most black bands in this country that were recorded were recorded like white bands, and they sounded like white bands. They used to record The Chants like a white pop band, which we weren't. We weren't musically adept enough in them days to establish what we really wanted ourselves - we weren't musicians then."

Eddie talks with some bitterness about this upon the career of The Chants, but at the end of the day, the other musicians could only bring the influences they had to the table, and that seems to have extended only as afar as the latest releases of the 'beat' and 'mod' scene - r&b influenced, to be sure, but too adulterated for what The Chants wanted. You do sense that Eddie is directing his ire more at their management and at A&R at Pye itself, who either from benign ignorance, or paternal condescension, did not put enough thought into how The Chants worked best, and didn't hire the kind of arranger and band that would have made a difference. With Pye unaware of The Chants best interests, as Eddie admitted, they were also too inexperienced to know how to ask for what they wanted.

So, during the 1960s, you can hear the sound of The Chants changing with the dominant trends of 60s British pop, and changing accompaniment, from Merseybeat ballads to psychedelic-tinged pop in the late 60s. Live, they continued to attract a loyal following, regularly performing at venues such as The Twisted Wheel in Manchester and touring Europe, where they played alongside Curtis Mayfield and The Four Tops at US Army bases in Germany. Whatever they tried, however, they still could not break into the pop market for commercial success. It is not entirely clear that even if they had hit the magic formula, that they would have profitted from that success. Geno Washington, who despite low single sales made a success of a series of 'live' albums, cashing in on his immense popularity on the live circuit, became embroilled in a legal fight over the royalties he was owed by Pye, a battle he lost and saw him bow out at the end of the 60s.

So, during the 1960s, you can hear the sound of The Chants changing with the dominant trends of 60s British pop, and changing accompaniment, from Merseybeat ballads to psychedelic-tinged pop in the late 60s. Live, they continued to attract a loyal following, regularly performing at venues such as The Twisted Wheel in Manchester and touring Europe, where they played alongside Curtis Mayfield and The Four Tops at US Army bases in Germany. Whatever they tried, however, they still could not break into the pop market for commercial success. It is not entirely clear that even if they had hit the magic formula, that they would have profitted from that success. Geno Washington, who despite low single sales made a success of a series of 'live' albums, cashing in on his immense popularity on the live circuit, became embroilled in a legal fight over the royalties he was owed by Pye, a battle he lost and saw him bow out at the end of the 60s. In their singles of the late 60s, The Chants developed messages into a number of their songs, perhaps in part inspired by the problems and barriers they had tried to overcome in their career. For the community of Toxteth, they continued to be feted, and in particular, local MP, 'Battling' Bessie Braddock, had strongly supported them ever since their first recording.

In their singles of the late 60s, The Chants developed messages into a number of their songs, perhaps in part inspired by the problems and barriers they had tried to overcome in their career. For the community of Toxteth, they continued to be feted, and in particular, local MP, 'Battling' Bessie Braddock, had strongly supported them ever since their first recording.The Chants - Progress

The Chants - You Don't Know What I Know

Throughout all of this, The Chants had to also make a living. Increasingly, they took bookings to perform less at the cutting edge of soul, and more on the cabaret circuit of popular standards mixed with a few of their Mersey hits. This way, the rest of the Chants could continue in music and put food on the table, but for Eddie Amoo, it was not what he had dreamt of. He began to perform less and less with The Chants, and made his way back to Toxteth, where he discovered a new possibility unexpectedly close to home. His younger brother Chris had formed his own band...

"The Real Thing started out with three people, then went to five, then they dropped two out and by 1975 they'd become a trio - Ray, Dave and Chris. But by then Chris [Amoo] and I had started to write together. I wrote the first three Real Thing singles. I was still with The Chants, but I was writing for The Real Thing, because The Chants were no longer a vehicle for the songs I was writing - The Chants were doing cabaret, and The Real Thing were able to play these songs live, so I was writing and giving the songs to Chris."

The Real Thing were more fortunate than The Chants had been in that they were able to secure the services of some people with experience of soul music, in the form of songwriter Ken Gold, who had written songs for Aretha Franklin, Jackie Wilson and Eugene Record, and producers such as Jerome Rimson, who had played with The Detroit Emeralds, Hugh Masekela and others. They also had the experience of Eddie Amoo, who wrote many of The Real Thing hits with his brother, to steer them away from decisions that might stymie their career.

The Real Thing were more fortunate than The Chants had been in that they were able to secure the services of some people with experience of soul music, in the form of songwriter Ken Gold, who had written songs for Aretha Franklin, Jackie Wilson and Eugene Record, and producers such as Jerome Rimson, who had played with The Detroit Emeralds, Hugh Masekela and others. They also had the experience of Eddie Amoo, who wrote many of The Real Thing hits with his brother, to steer them away from decisions that might stymie their career.Such considerations were important, for essentially, the mass commercial appeal of 'soul music' had begun to dissappear not long after the 'mod' heyday of 1965-66, and by 1967, new influences focused more on the psychedelic scene had taken their place in British youth culture. It is important to remember that youth cultures in those times were not fuelled by 20 and 30-somethings living an eternal youth, but by teenagers just entering the world of work. In 1970, 95% of people under the age of 45 in Britain were married, and embarking on a new family life, which did not involve following the latest musical trends. An entire generation who had been inspired somewhat by soul music had essentially 'grown up' and settled down, sometimes casually tuning into Tony Blackburn on Radio 2 to hear some old Motown hits. It wasn't until the mid 70s that a new disco-influenced soul began make an impression on the record-buying public, who were by then a quite different generation of teenagers.

This time, the band set out deliberately to write those hit records, and they succeeded time after time, with classic disco soul like You To Me Are Everything and Can You Feel The Force in which even Pye Records could not fail to see the potential. Beneath the surface of success, however, the band yearned to venture further into funk and to write lyrics with a wider meaning. By the mid 70s, racial tensions in Toxteth were building to levels not experienced since 1948, despite the outlawing of overt racial discrimination The Race Relations Act. Britain was in the midst of yet another period of economic decline after a short respite of the early 70s, Merseyside itself was suffering a major slump, and many people looked around for easy explanations. While small in actual number, the National Front were a prominent and highly vocal group, and their activities in the mid 1970s validated a much larger swathe of petty prejudices amongst white Britons. Levels of unemployment were higher in Liverpool 8 than in the surrounding districts, as people struggled. Housing, welfare and education in Toxteth was maintained badly by a bankrupted council increasingly preoccupied by ideological disputes about socialism. Meanwhile, Merseyside Police were becoming increasingly heavy-handed with the application of stop and search powers. It was in this environment that The Real Thing wrote their masterpiece, Children Of The Ghetto. Sadly, the song's call for action to change conditions were ignored, and political interest in the difficulties of Liverpool 8 would only be pricked by the Toxteth Riots in 1981.

The Real Thing - Liverpool Medley: Liverpool 8/Children Of The Ghetto/Stanhope Street

Today, Joe Ankrah, who also left The Chants in the 1970s to perform with Ashanti with brother Edmund, is a respected artist, working and living in Liverpool 8. Eddie and Chris Amoo still tour with The Real Thing. Bizarrely, one of their former tour bassists, Des Tong, went on to form a computer company, and devised some of the motion-capture technology that is used in film and animation today.

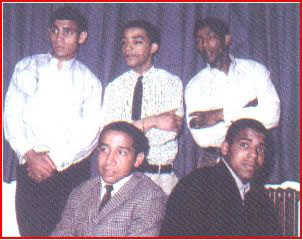

Today, Joe Ankrah, who also left The Chants in the 1970s to perform with Ashanti with brother Edmund, is a respected artist, working and living in Liverpool 8. Eddie and Chris Amoo still tour with The Real Thing. Bizarrely, one of their former tour bassists, Des Tong, went on to form a computer company, and devised some of the motion-capture technology that is used in film and animation today. Information about the Chants came from excellent articles by Bill Harry, Des Tong, and The Soulpool website. Bessie Braddock photo by Bert Hardy/Getty Images. Chants photos courtesy of Bill Harry and Des Tong. Dave Haslam has written a particularly good article and interview with Eddie Amoo about The Real Thing. You can buy "The Real Thing: Children Of The Ghetto - Greatest Hits" direct from itunes.

Information about the Chants came from excellent articles by Bill Harry, Des Tong, and The Soulpool website. Bessie Braddock photo by Bert Hardy/Getty Images. Chants photos courtesy of Bill Harry and Des Tong. Dave Haslam has written a particularly good article and interview with Eddie Amoo about The Real Thing. You can buy "The Real Thing: Children Of The Ghetto - Greatest Hits" direct from itunes.