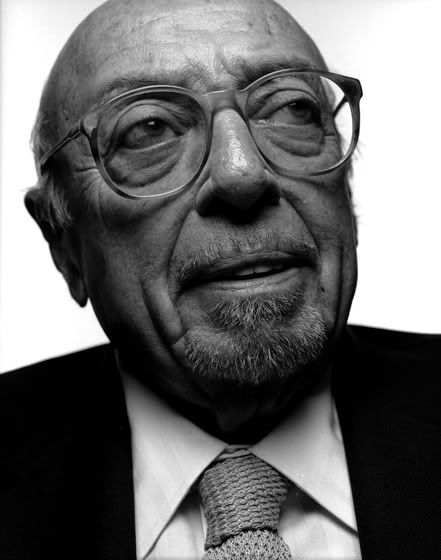

The tribute concert to commemorate the life of Ahmet Ertegun has been postponed until December 10th. The announcement that Led Zeppelin would reform to headline the show sent rock fans into a frenzy for a furious ticket lottery earlier this year, perhaps to the detriment of the memory of Mr Ertegun himself, who sometimes was barely mentioned in the news reports.

The tribute concert to commemorate the life of Ahmet Ertegun has been postponed until December 10th. The announcement that Led Zeppelin would reform to headline the show sent rock fans into a frenzy for a furious ticket lottery earlier this year, perhaps to the detriment of the memory of Mr Ertegun himself, who sometimes was barely mentioned in the news reports. So here for your enjoyment are some more nuggets of Nugetre ("Ertegun" backwards), r&b authored by Ahmet himself, continuing the series I ran last November. Well, this selection has a few twists and turns, which took it past Ahmet along the way...

So here for your enjoyment are some more nuggets of Nugetre ("Ertegun" backwards), r&b authored by Ahmet himself, continuing the series I ran last November. Well, this selection has a few twists and turns, which took it past Ahmet along the way... Whatcha Gonna Do by The Drifters was recorded on 2nd April 1954 and was released in February 1955 and featured Clyde McPhatter on lead vocals, and was to become the last single featuring him, as several other recorded tracks were then canned and kept for rainy days and b-sides. It reached No.2 on the R&B chart. It marked the end of Clyde's tenure with the group, as it had been intended to promote it as a commencement of his solo career. Then in July 1955 he was drafted.

Whatcha Gonna Do by The Drifters was recorded on 2nd April 1954 and was released in February 1955 and featured Clyde McPhatter on lead vocals, and was to become the last single featuring him, as several other recorded tracks were then canned and kept for rainy days and b-sides. It reached No.2 on the R&B chart. It marked the end of Clyde's tenure with the group, as it had been intended to promote it as a commencement of his solo career. Then in July 1955 he was drafted. This was the third time that the Drifters had recorded the song, the first time having been with the short-lived Mount Lebanon Singers line-up, the next time when Bill Pinkney and the Jerusalem Stars had come in to replace the Mount Lebanon Singers on 9th August 1953. So in a way the song had a history that spanned the entire period of the classic Drifters line-up. It also had a gospel past.

This was the third time that the Drifters had recorded the song, the first time having been with the short-lived Mount Lebanon Singers line-up, the next time when Bill Pinkney and the Jerusalem Stars had come in to replace the Mount Lebanon Singers on 9th August 1953. So in a way the song had a history that spanned the entire period of the classic Drifters line-up. It also had a gospel past. Whatcha Gonna Do was originally recorded by The Radio Four, and written by their lead singer Reverend Dr Morgan Babb. Ahmet had heard the gospel tune perhaps on the legendary radio show Ernie's Record Parade, John Richbourg's show on WLAC on a 50,00 watt signal out of Nashville, as Dr Babb also acted as a gospel A&R man for Ernie Young, founder of Nashboro and Excello Records, who was the show's sponsor.

Whatcha Gonna Do was originally recorded by The Radio Four, and written by their lead singer Reverend Dr Morgan Babb. Ahmet had heard the gospel tune perhaps on the legendary radio show Ernie's Record Parade, John Richbourg's show on WLAC on a 50,00 watt signal out of Nashville, as Dr Babb also acted as a gospel A&R man for Ernie Young, founder of Nashboro and Excello Records, who was the show's sponsor. This 45 was recorded at 535 Fourth Avenue South in Nashville and released in April 1953 on Tennessee Records subsidiary label Republic. The new subsidiary had been set up in summer 1952 on the back of the success of Christine Kittrell's single Sitting And Drinking. The five brothers in the group, of whom Dr Babb was the youngest, had been performing in various line-ups since the late 1930s. The Radio Four had an enviable reputation in the gospel circuit, regularly sharing billing with R.H. Harris' Soul Stirrers, and by chance happened to be double-heading the bill for Sam Cooke's first outing with the Stirrers. They recorded a kind of country gospel style, which related very much to the older brothers' former days in a popular jug band before their conversion to religion (appparently due to a bolt of lightning that nearly killed their father.) When Dr Babb joined his older brothers in 1950, he brought a emotive, soulful style of singing, which set them apart from the emphasis on technical singing found in the jubilee singing groups of the era.

This 45 was recorded at 535 Fourth Avenue South in Nashville and released in April 1953 on Tennessee Records subsidiary label Republic. The new subsidiary had been set up in summer 1952 on the back of the success of Christine Kittrell's single Sitting And Drinking. The five brothers in the group, of whom Dr Babb was the youngest, had been performing in various line-ups since the late 1930s. The Radio Four had an enviable reputation in the gospel circuit, regularly sharing billing with R.H. Harris' Soul Stirrers, and by chance happened to be double-heading the bill for Sam Cooke's first outing with the Stirrers. They recorded a kind of country gospel style, which related very much to the older brothers' former days in a popular jug band before their conversion to religion (appparently due to a bolt of lightning that nearly killed their father.) When Dr Babb joined his older brothers in 1950, he brought a emotive, soulful style of singing, which set them apart from the emphasis on technical singing found in the jubilee singing groups of the era. This particular track also bore the name of Madame Edna Gallmon, a bone of contention for The Radio Four. Morgan Babb had helped her to get a chance singing with them at Tennessee, and coached her in technique to develop an up close and personal style of performance. The first recordings were released released as just by The Radio Four, as Tennessee were unsure whether to even sign her to a contract. When she was finally signed, not for the first time Tennessee wanted to use them as a backing group for the new 'star', and so The Radio Four stated that they would not be backing her in the future. Despite this, tracks like this one were later released and promoted with both Gallmon and The Radio Four's names. To add further salt to the wound, Dr Babb was never paid any royalties for the songs , like this one, that he wrote for Republic.

This particular track also bore the name of Madame Edna Gallmon, a bone of contention for The Radio Four. Morgan Babb had helped her to get a chance singing with them at Tennessee, and coached her in technique to develop an up close and personal style of performance. The first recordings were released released as just by The Radio Four, as Tennessee were unsure whether to even sign her to a contract. When she was finally signed, not for the first time Tennessee wanted to use them as a backing group for the new 'star', and so The Radio Four stated that they would not be backing her in the future. Despite this, tracks like this one were later released and promoted with both Gallmon and The Radio Four's names. To add further salt to the wound, Dr Babb was never paid any royalties for the songs , like this one, that he wrote for Republic.Listen to a rollicking, boogie-woogie number:

Clyde McPhatter & The Drifters - Whatcha Gonna Do (Atlantic 1055) 1955

And here is the gospel original:

Mdm Edna Gallmon Cook & The Radio Four - Whatcha' Gonna Do? (Republic Records 7067) 1953

OK, I can understand Led Zeppelin being on the bill. But Paolo Nutini?

I really enjoyed researching this little post, as I discovered so many connections between this and other artists I had researched in the past year. Information and images about The Drifters from Marv Goldberg's R&B Notebooks, a site I cannot stop reading! Information about The Radio Four comes from the liner notes of CD The Radio Four 1952-1954, written by Opal Louis Nations, which is also where I took the featured track from. The great gospel site Recordconnexion, written by Robert Termorshuisen, who got details from ''Gospel Music 1943-1969' by Cedric Hayes and Robert Laughton, is also a great resource. I also read about Dr Morgan Babb on the WLAC Fan Site. The Radio Four label scan and images come from Big Joe Louis and Robert Termorshuisen. The development of gospel in Tennessee is well documented by PBS in the article From Jug Band To Gospel by David Evans & Richard M Raichelson Also, visit this post at Red Kelly's gospel blog, Holy Ghost, to read a bit more about Nashboro Records.

RIP Bill Pinkney, 15th August 1925 - July 4th 2007

RIP Bill Pinkney, 15th August 1925 - July 4th 2007